Teaching PPO Agent to Play Flappy Bird with SB3/Gymnasium

Introduction

Hello fellow reader!

I am writing this post to report and document a little side project I worked on during Christmas to gain proficiency in two of the tools I will be using throughout my Ph.D., namely: Stable Baselines 3 (SB3) and Gymnasium (Gym).

My thought process was that since I need to learn many tools and frameworks to actually start working on Contact-Rich HRM with RL, I should try to isolate a few tools so that I don’t become overwhelmed. To do so, I chose to leave Robots aside for a bit, and lean on a much simpler environment with only 2 actions: the game Flappy Bird ! The video shown above is my final agent trained with Proximal Policy Optimization (PPO) at around 920k steps. The agent can achieve a score of 40, although it sometimes fails early for reasons I am not sure about.

Although there are countless Gym environments available on the internet, I figured using a premade environment would make this project too easy. Additionally, I will not be using premade environments in the future, so I made the conscious choice to design my own environment. I took a working game with Pygame from a repository, meant to be played by humans, and modified it into a fully working Gym environment.

Finally, the choice of algorithm and low level RL stuff was not explored for simplicity’s sake. As such, I used SB3’s PPO implementation with a Multi-Layer Perceptron (MLP) policy. I chose PPO without much thought into it. I chose it over Soft-Actor Critic (SAC) because SAC is not compatible with discrete action spaces such as the one in this environment.

In the rest of the post, I will elaborate various topics such as:

- Using custom environments;

- Observation and Action Spaces;

- Reward Shaping;

- Acknowledged issues and ways to make the problem more interesting.

Using Custom Environments

All environments in Gym must inherit from a parent class gym.Env and follow the following structure:

class FlappyBird_v1(gym.Env):

def __init__(self):

# Initialize positions - will be set randomly in reset()

# Define what the agent can observe,

self.observation_space = gym.spaces.Box(low=-np.inf, high=np.inf, shape=(5,), dtype=np.float32)

# Define what actions are available (0: do nothing, 1: flap)

self.action_space = gym.spaces.Discrete(2)

# # Initialize other things that need to be initiliazed only once

...

def _get_obs(self):

"""Convert internal state to observation format.

"""

return observations

def _get_info(self):

"""Compute auxiliary information for debugging.

"""

return info

def reset(self, *, seed: int | None = None, options: dict | None = None):

"""Start a new episode.

Reset the environment into the start state of an new episode.

"""

super().reset(seed=seed)

# Reset state and return initial observation/info

observation = self._get_obs()

info = self._get_info()

return observation, info

def step(self, action):

"""Execute one timestep within the environment.

"""

# Compute one environment step

# Compute step reward

# Execute given action

terminated = self.done

truncated = False

observation = self._get_obs()

info = self._get_info()

return observation, cumulative_reward, terminated, truncated, info

This structure consists of 4 mandatory methods and 1 auxiliary method:

__init__

The _init_ method includes all variables and mechanisms that need to be initialized only once. These include:

- Defining the environment observation space (types of spaces);

- Defining the environment action space (see URL above);

- Define other variables, environment logic and flows that need to be initialized only once:

- Initialize Pygame.

TODO: Add reference to observation and action spaces

Like any other __init__ method of a Python Class, this method is only executed on class instance creation.

reset

The reset method resets the environment to an initial state, which is required before calling step in a new episode. It returns the first agent observation for an episode and information. Here…

- It resets the bird’s instance;

- Clears the list of existing pipe pairs;

- Compute environment observations;

- Resets frame clock, game score and done/terminated from a previous episode.

step

The step method is where the major chunk of the environment logic resides. It updates the environment with a given action, returning the next agent observation, the reward for taking that action, whether the environment has terminated or truncated due to the latest action, and information from the environment about the step.

In this environment, in very simple terms, step does the following:

- Check whether to add a new pipe pair to the environment;

- Executes given action (Flap or do nothing);

- Checks for collisions;

- Computes step cumulative reward;

- Computes environment observations;

- Updates game score.

_get_obs

This helper method translates the environment’s internal state into the observation format. This keeps the code DRY (Don’t Repeat Yourself) and makes it easier to modify the observation format later.

TODO: Add reference to observation and action spaces

_get_info

Sometimes some data is only available inside Env.step() (like individual reward components, action success/failure, etc.). In those cases, it is useful to record this information to debug or for visualization purposes. The _get_info helper method is executed at the end of both step and reset and can contain a miscellaneous collection of information deemed to be useful when debugging.

Making an environment compatible with Gym

With the proper structure of a Gym environment discussed, I can now explain how to make a pre-existing environment compatible with Gym. To start, one must take a step back and think about which parts of our environment execute only once, which are part of the main game logic loop, and which parts would need to be reset for a new episode to begin. After identifying these, the code needs to be split into the aforementioned methods __init__, step and reset, respectively. Due to the object-oriented programming (OOP) nature of Gym, environments need to be adapted to be class-friendly, in part due to the limited scopes of each of the aforementioned methods.

Observation and Action Spaces

Every RL agent needs a set of observation and possible actions. The possible actions in this game are either to flap or to do nothing and let gravity bring the bird down. Therefore, the action space was defined as a discrete action space given by the set $\mathcal{A}=\{0,1\}$, with 1 corresponding to flapping and 0 corresponding to doing nothing. There was a slight caveat that the original environment did not account for, that is the possibility to spam flaps which would cancel each other out and make the bird effectively float. This was fixed by adding a delay corresponding to the flight duration in which the action flap is nullified. One big problem I found in the beginning was that the game rendered at 60FPS, which meant 60 actions each second. In early training, both actions are taken with similar probability, and in order to maintain an average stable $Y$, the agent needs to do nothing for about 95% of steps. This led to problems with always hitting the top border. There was some thought put into modifying the action space to either flap or rest for $n$ steps. In the end, I tackled this problem through reward shaping (which is covered below), but this alternative approach may also have led to success.

Regarding observation spaces, there was the choice between full and partial observability. Full observability would imply giving all available state information to the agent. This option has a greater performance ceiling, but comes with a ton of extra noise which would make training difficult and require fancier image processing mechanisms such as convolutional autoencoders to reduce dimensionality and extract relevant features, thereby reducing unnecessary noise. Here full observability would entail giving the game window, as well as other internal variables. Since this is a relatively simpler environment, I chose to stick with partial observability and hand-craft the features. The list of features I settled on were the following:

- Bird’s vertical position (y-coordinate)

- Next pipe’s horizontal distance (how far away)

- Next pipe’s gap vertical position (top/bottom of opening)

- Bird’s distance from top/bottom of screen (helps avoid boundaries)

This kept the agent simple and without any unnecessary information. The idea was to give only what the agent needed to rely on to make a decision. Constants like the gap or width of a pipe pair, bird’s hitbox, and bird’s x-coordinate are not needed as the agent can learn those internally.

Reward Shaping

Perhaps the most interesting and challenging aspect of this project. Coming from theoretical literature, I learned that giving intermediate rewards to an agent is not ideal as it incentivizes a certain policy we think is best, while there may be a better policy that we are not capable of seeing. In classical RL learning problems, such as the maze problem, rewards are typically only given at the goal state. In real problems, this often leads to such a sparse reward that agents simply cannot learn. As such, here is the reward design I chose:

- Small survival reward -> $+0.01/step$ meaning $+6/s$;

- Big reward for clearing a pipe -> $+300$;

- Big punishment for colliding with either pipe or top/bottom borders -> $-500$;

- Exponential punishment for consecutive flaps -> $2 + (n_{consecutiveFlaps}^2)*0.01$

The punishment for consecutive flaps was a way of dealing with over-flapping in the beginning as I previously mentioned. One issue I had initially was a completely wrong scale that disregarded framerate. I was giving a survival reward of $2$, which meant $120/s$. This taught the agent that surviving was more important than clearing pipes, so the agent did not get very far. Another problem I had was finding a correct scale for the rewards. These numbers I came up with came from thin air. While it worked, I wonder what other ways there are to optimize reward scaling.

Results & Discussion

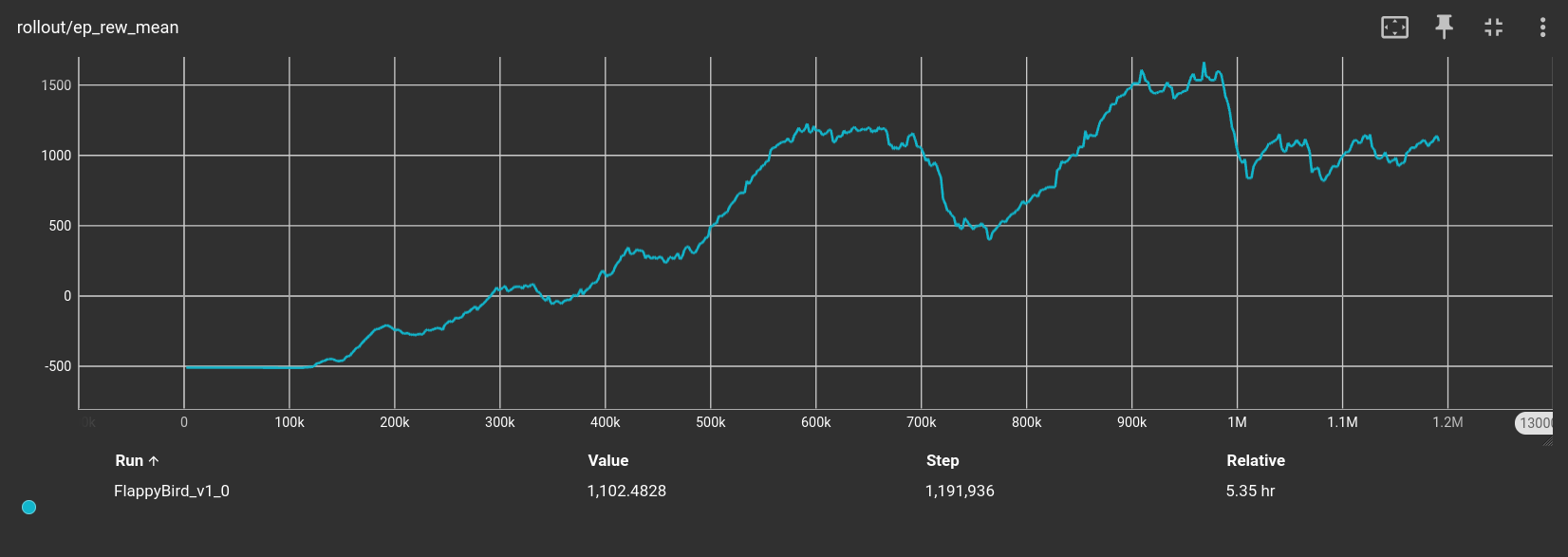

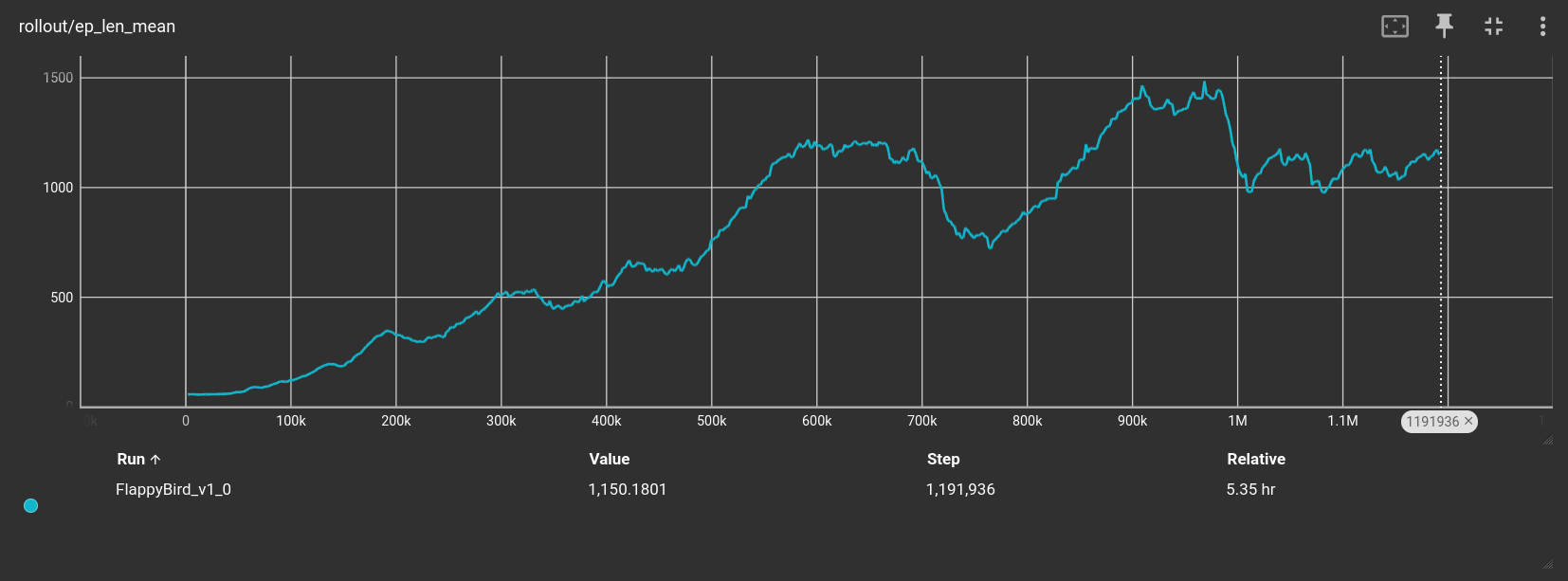

Using Stable Baselines 3’s features, I saved TensorBoard logs every $10k$ steps. Here are both the mean reward and mean episode length across steps:

Both plots show how the agent learned well the environment. At around $700k$ and $1M$ steps there were some hiccups. For the demo I chose the model at $920k$ steps, as it seems to be the most stable. Nevertheless, there are still many improvements to be made. The agent achieves a score of $20-40$ every few runs but in between gets stuck in the first few pipes and makes blunt mistakes. I am not sure why after going through the first, the agent seems to be much more stable. Additionally, whenever the agent fails, it is very often due to bumping its head on the corner of the up pipe when exiting.

On the technical side, on future experiments, I would like to implement a way to start training from other trained models rather than from scratch.

This environment can be made harder in many ways, whether through smaller or variable gaps, varying or greater horizontal velocity, less spacing between pipes, etc. However, I think this is a good breakpoint to move on to other more interesting things, such as messing with Robots again.